Methods Overview

You have already heard the term methods and already have created some. This chapter explains methods a bit more. Remember we created a method in step 3 of our 5-Step Solution Algorithm. Methods are an extremely important programming concept.

Dividing your code into logical sections, makes your code easier to read and debug. My code examples contain methods. Simplistically stated, when you divide your program into logical blocks of code, it is modularized. Each method should have one primary task. Limiting the task that a method does, makes the method efficient and reusable.

What are Methods?

Methods have also been called modules, functions, subroutines, subprograms, and procedures. The term you use in part depends on your development language. For instance, JavaScript uses the term functions. However, Java and C# developers typically use the term methods. Many old-school programmers use the terms module and method interchangeably and reserve the term function for a method that returns a value. Just remember, in Java and C#, the term used is methods.

We use methods because they are a great way to organize code so it is easier to read and maintain. Further, modularized code can be re-used either within the same program (by calling the method multiple times) or in a different program via imports or copy/paste. Also, we learn methods in preparation for more advanced coding procedures such as Objected Oriented Programming.

In short, methods are used to break a problem into small manageable parts. Basically, divide and conquer should be your mantra when designing methods. One rule of thumb is, if you find yourself writing the same code, or nearly the same code again and again in your program, you should put the repeated code into a method.

(Re)usability

Re-usability is definitely something to strive for when designing your methods. That is why I said “...or nearly the same” instead of exactly the same. Think about the error messages you have seen. Basically, all error messages just display text. However, many students think they need a different method for the different types of errors. This is not the case. All you really need is one method that takes in (at least) the error message as a parameter and displays the message.

Typically, error messages, end-user validation and database connectivity code are excellent candidates for modularization. Think about it, every time the end-user submits data you need to validate their submission. With database connectivity, you do not want to type the connection string over and over, so you put the connection code in a re-usable method.

Method Signatures (a.k.a. Headers or Definitions)

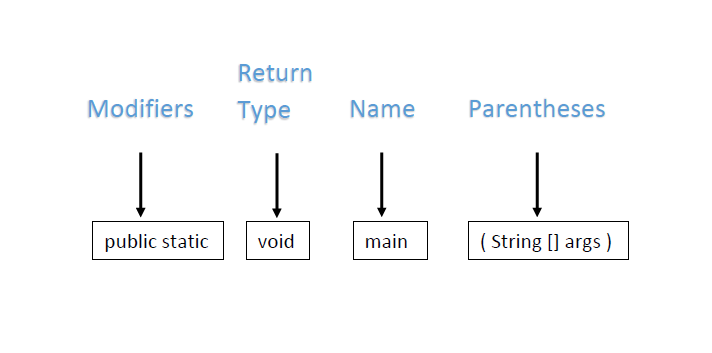

The anatomy of a method may look difficult to get your head around, but in reality, each method is made up of the same pieces parts. It is your responsibility to appropriately name your method, pick the needed modifier, determine if a value should be returned, and if parameters are needed. Notice from my examples below, the data inside of the parentheses can change. Remember, data inside the parentheses is generically called parameters.

Each method signature contains

the following:

Return Type

Method Name

Parentheses (with or without parameters)

Method main()

Please study the below image. Same as always, method main() is where our programs begin. The keyword public is a modifier that means the method can be used by code that is outside of its containing class. However, we never call main(), it is automatically called by the Java engine. The main() method should always be public. Notice this method also uses the modifier static, which means the method belongs to the class and not a specific object. Although other methods can be static, in this course, the only static method we create is the main() method. You should not alter the signature of the main() method.

Below is the Java code for our Main class with its main() method. Notice the Controller class is being instantiated. In Program Logic, your Main class and main() method should always look like this. Please study the code below.

public Class Main(){

public static void main(String[] args) {

Controller control = new Controller();

}//end main method

}//end class

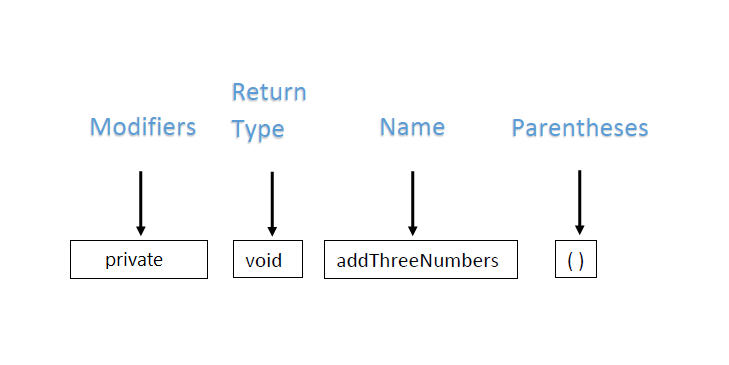

Void Methods

Please study the below image. When the return type of a method is void, the method will not return anything to its caller. In this course, we will use private as the access modifier for all our methods, accept the main() method and constructors. An access modifier of private means that your method cannot be seen outside of its containing class. Our containing class is the Controller. Please note, you could have parameters inside of the parentheses.

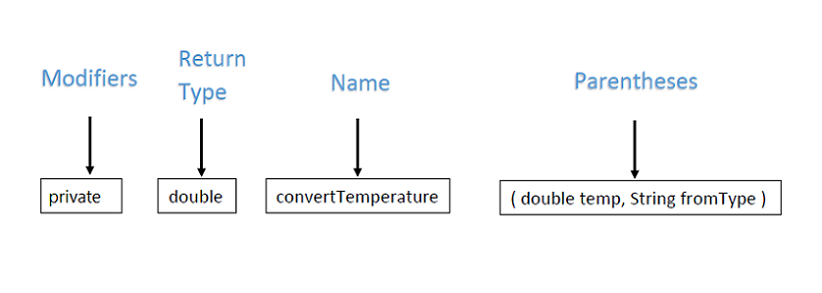

Methods that Return a Value

Not all methods have void as their return type. You can specify a return type, such as double, String, or int. Remember in this course, we will use private as the access modifier for all our methods accept for main() and constructors. Also take note in this method signature, more than one parameter is being sent into the method. Each parameter is listed between the parentheses, with its data type and separated by a comma. When you create a method that accepts parameters, the method signature must include the data type for each parameter.

Also remember, just because a method returns a value does NOT mean it must accept parameters. Quite often this type of method does accept parameters, but, it is not a requirement. However, if a method returns a value, you must have a variable of the same data type to catch the returned value. Below is a code snippet of a call to a method that returns a value. Notice the variable covertedTemp is “catching” the returned value. Please study the code below.

double convertedTemp = 0.0;

convertedTemp = convertTemperature(numToConvert, celsius);

Constructor

Think about setting up your NetBeans projects. Our Controller class contains a constructor. A constructor is a special method that MUST be named the same as the class it is within. The constructor must NOT have a return type and in this course, the constructor should always have public as its access modifier. Please study the below code example of a constructor named Controller() nested inside of a class named Controller. Please study the code below.

public class Controller{

public Controller(){

//call to a method goes here

}//end constructor

}//end class

As the name implies, the constructor constructs or builds the class. When a constructed class is instantiated it is then referred to as an object. In Program Logic, our constructor has a call to a method that kicks off the processing for the assignment.

Access Modifiers

You may still be sketchy on the modifiers. Let's just say in Program Logic, you should not change the modifiers for our main() method. In fact, you can let our development environment create the main() method for you. Except for the constructor, methods in the Controller class should be designated as private. Just in case you are curious, the following table shows you some valid Java modifiers. Please study the table below.

| Access Modifier | Description |

|---|---|

private |

Only code within the same class has access. |

public |

Accessible by code in any class. |

| no keyword | This is Java's default modifier. Available to any other classes in the same package. |

protected |

Accessible to subclass in another package and any class within its package. |

One Primary Task

The primary task of the constructor is to constructor or build the class. For our purposes, building the class means that the method you want to run first should be called from the constructor. Why? Because the code in the constructor gets run immediately after the instantiation of the class. Remember, instantiate means you called the class using the keyword new. We have been instantiating our Controller class inside of our main() method since the beginning of the semester.

Many times students try to make their methods perform one and only one task, such as add three numbers. However, it is much more practical to think in terms of one primary task. Looking back at our solution algorithm chapter, you will see my methods do three tasks. The primary task that solves the problem, such as adding three numbers. The needed task of getting those numbers from the end-user, and the final task of displaying the sum.

It possible to divide and conquer the tasks into separate methods. But is it necessary? For learning purposes, yes. I combined the tasks within one method called addThreeNumbers() to keep it simple, after all, at that point, I had not discussed methods.

Here are likely method names if I practice the divide and conquer tactics. Remember, method names should start with a verb. Also in Java, the first “word” of the method name starts with a lowercase letter and subsequent “words” start with an uppercase letter. In programming, this naming convention is typically called camel case.

addThreeNumbers

displayResults

Calling a Method

It is not enough to just code a method, you also need to call the method. Think of it this way...you call a method into action. When the method is a class constructor, you instantiate a class and the constructor is automatically called. But for your custom methods, you must explicitly call the method. You call a method when you want to run the code within the method. Remember, order matters! Based on the calls below, you would not want to call displayResults() before you actually had results to display. A method just sits there waiting to be called into action, so it does NOT matter which order your methods are written within the class. It is the order of the calls to the methods that matter.

It is also important to remember not all methods need to be called from the constructor. It may make more sense to call a method from within another method. If the method you are calling needs parameters to run, then you want to call the method AFTER you have obtained the values for the parameters. Remember variable scope. A variable lives and dies within the method it is created in unless you pass the values to another method.

getUserInput();

addThreeNumbers(num1, num2, num3);

displayResults(sum);

Arguments and Parameters

Remember how a method signature always includes the parentheses and that the parentheses have zero or more parameters? Well, if the method is expecting parameters, you need to supply them. Technically, the data supplied in the call is referred to as arguments. When the data is received in the method signature, the data is referred to as parameters.

IMPORTANT! The data types of the arguments AND the order of the arguments MUST MATCH the data types of the parameters AND the order of the parameters. This is because their names do not matter. Remember, variable names are for our benefit.

Please study the method calls below. Notice which methods include arguments. Arguments must be defined prior to the method call.

getUserInput();

addThreeNumbers(num1, num2, num3);

displayResults(sum);

Order Matters!

Logic must prevail when calling methods. Looking at the above method calls, the addThreeNumbers() method needs three variables because the call is sending three arguments. But where are the variables declared? Logically speaking, they are declared in the method getUserInput(). It is also safe to assume that getUserInput() supplies values to the variables num1, num2, and num3. Remember variable scope. Since the variable values are supplied within getUserInput(), then it is logical to assume the call to addThreeNumbers() happens when those variables and their values are known. In other words, after all the variables have their values, call addThreeNumbers() passing it the variables.

Let's spin the logic out a bit further. Based on our example, the variable sum should get its value AFTER the three numbers are added together. The code may look something like: sum = num1 + num2 + num3; Following the example, it is safe to say that displayResults() is called after sum has its value.

Logically, you could:

- call

getUserInput()from within the constructor - call

addThreeNumbers()from withingetUserInput(), but AFTER the variables have valid values. - call

displayResults()from withinaddThreeNumbers(), but AFTER the variablesumhas a valid value.

Please study the code snippets below. They put together the logic and show the flow of the code. Pay attention to the comments on my ending curly braces. These are there to help write the code in the correct spot. Remember, curly braces on a method say, all this code belongs together.

public Class Controller{

public Controller(){

getUserInput(); //method call

}//end of constructor

private void getUserInput(){

//declare and initialize the variables

double num1 = 0.0;

double num2 = 0.0;

double num3 = 0.0;

//get values for each number from the end-user

addThreeNumbers(num1, num2, num3); //method call

}//end of getUserInput()

private void addThreeNumbers(double num1, double num2, double num3){

//declare and initialize the variable

double sum = 0.0;

sum = num1 + num2 + num3;

displayResults(sum);

}//addThreeNumbers()

private void displayResults(double sum){

System.out.println("The sum of your numbers is: " + sum);

}//end displayResults()

}//end of class

What You Learned

- You learned that ORDER MATTERS!

- You learned that methods are a way to organize code and that a method should have one primary task

- Method signatures must include parentheses, but they can be empty

- Method

main()is the onlystaticmethod we create in this course - You learned you should not change the signature of method

main() - You learned that

privateandpublicare access modifiers - You learned that some methods return a value and some do not

- You learned the difference between parameters and arguments

- You learned how to call a method

- You learned that the constructor is a special method that is automatically called when you instantiate its class

What's next?

The next chapter in this unit is: Void Methods